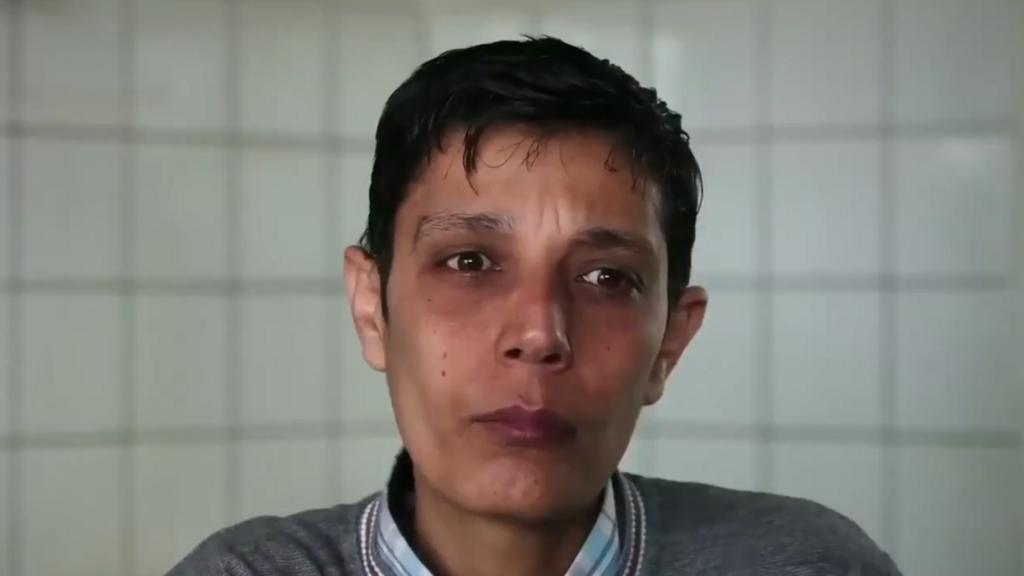

His gaunt face and haunted eyes have once again become a symbol of Syrian resistance. The body of Mazen al-Hamada, a former prisoner of Bashar al-Assad’s security services and an early activist in the 2011 Syrian uprising, was found on Monday in the Harasta Military Hospital morgue near the capital Damascus.

“This body is very similar to that of detainee Mazen al-Hamada,” the NGO Syrian Revolution Archive posted on Instagram alongside a photo of his body.

Mohammed al-Hajj, a fighter with one of the rebel factions based in the country’s south, told AFP that searchers had unearthed dozens of bodies.

“It was a terrible sight,” he said. “Forty-odd bodies were piled up on top of one another, showing signs of terrible tortures.”

The news of Hamada’s death shocked those who had followed the activist’s work. He spent years travelling across Europe and the US, trying to bring more attention to the widespread abuses committed by Assad’s security services. Hamada had not been heard from since his abrupt return to Syria in 2020.

“I need to get more information, and have time to process this utterly devastating news,” British journalist and filmmaker Sarah Afshar, who made a documentary about Hamada in 2017, wrote on X. “I want to remember Mazen the way he was, and to honour what he did.”

Broken ribs and sexual abuse

Born in Deir Ezzor in Syria’s northeast in 1978, Al-Hamada was 33 years old when the uprising against Assad began in 2011.

“In Syria, I was one of the founders of the protest movement,” he said in one interview.

The youngest child of a sprawling family, he worked as a technician for oil and gas multinational Schlumberger. Hamada filmed some of the first demonstrations against Assad on his camera, sharing the footage across social media.

The Assad regime’s response was not long in coming. On March 24, 2011, Hamada was arrested by security services and imprisoned for two weeks. A month later, he was detained again.

In March 2012, security agents picked him up from a Damascus café and took him to the Air Force intelligence branch of al-Mezzeh Military Airport. Transferred to the nearby 601 Military Hospital, Hamada recounted seeing bodies piled up in bathroom stalls. Other detainees were killed in front of him – seemingly at random.

Read moreSednaya prison: ‘No sign of detainees, other than those who have already been freed’

Altogether, he spent some 15 months in detention. He was brutally interrogated and pressured to confess to terrorism-related charges. Hamada refused.

“They took me and they laid me on the ground and broke my ribs,” he said in Afshar’s documentary “Syria’s Disappeared: The Case Against Assad”. “He (the interrogator) would go up and jump on me. I’d feel my ribs breaking … He hung me [by my wrists], 40 centimetres off the ground. The weight is all on your hands, on the joints. So the handcuffs, when they get tight, you feel like they’re going to cut your hands off.”

He recalled security agents raping him with a metal pole and subjecting him to other forms of sexual torture.

“They locked a plumbing clamp around my penis and began to tighten it more and more,” he said.

“Lots of people have died from torture [in Syria].”

Hamada was freed by a judge in September 2013 and fled the country alongside millions of Syrians who left for Turkey, Lebanon or Europe. He crossed the Mediterranean to Turkey in 2014, eventually reaching the Netherlands, where he applied for asylum.

It was in Europe that he began his campaign to bring attention to the crimes of Assad’s regime. He played a central role in Afshar’s 2017 film, which documented the tens of thousands of Syrians detained, tortured and often killed in the government’s prisons.

The unimaginable return

Supported by a number of NGOs, Hamada travelled through Switzerland, France and Italy to accompany the exhibitions showing the work of a whistleblower known only as Caesar, a Syrian police photographer who had escaped to Europe with proof of the suffering inside Assad’s prisons. He testified before the US Congress of the horrors he had been subjected to at the hands of the regime’s security services.

“I won’t rest until [my torturers] are brought to justice,” he said in Afshar’s film, his eyes heavy with tears. “Even if it costs me my life, I will hunt them down and see them brought to justice, no matter the price.”

But Hamada, traumatised and increasingly despondent, struggled to rebuild his life in Europe.

“He had been losing his spirit for months,” French journalist Garance Le Caisne told regional daily paper Ouest-France. “He insulted everyone. He was worn out by the cowardice of the West.”

Worried by Hamada’s worsening mental health, Le Caisne decided to end her effort to collect his testimony. She would later publish what information she had already gathered in her 2022 book, “Forget his Name: Mazen al-Hamada, Memoirs of a Missing Man”.

Read moreThe road to Damascus: Syrian exiles return home to celebrate the fall of Assad

Hamada made the choice to return to Syria in February 2020, convinced that he would be more useful in his homeland than in exile. He disappeared as soon as his plane touched down in Damascus. His friends would never hear from him again.

“Did someone dangle something in front of him? We don’t know,” Le Caisne said. “In any case, he couldn’t have made it to Damascus without the regime giving the green light.”

When news of his death broke on Monday, images of Hamada’s face began to flourish across social media, shared by Syrian activists. For many, his drawn features will remain a symbol of his defiance in the face of Bashar al-Assad’s now-fallen regime – and the depths to which that regime was once willing to sink.

This article has been adapted from the original in French by Paul Millar.

Leave a Comment