A mound made up of dirt and rocks blocks the end of the main street. A few hundred metres further down, an even larger man-made black mound stands out against the horizon. The sound coming from the excavators digging nearby is loud and constant.

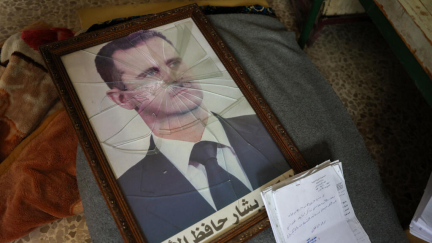

“They’re digging a trench that is three metres wide and six metres deep,” Ahmed Ali Tahar, mayor of the tiny village of Al-Hurriyah, in the governorate of Quneitra in the Syrian Golan, explains. “They started four months ago, as if they knew that Bashar (al-Assad) was going to fall.”

The construction project is enormous. Al-Hurriyah’s last house on the Syrian Golan Heights is now located just 500 metres from the Israeli border. Before, it was two kilometres away.

Israel announced in October, 2023, that, in a bid to prevent terrorist attacks like the one that Hamas had just unleashed from Gaza, it planned to fortify the so-called Alpha Line that separates the Israeli-occupied Golan from Syria.

‘Israel has spoiled our joy’

But on December 8, 2024, everything changed for the 1,000 residents living in Al-Hurriyah. “We were so happy about the fall of Bashar, but Israel spoiled our joy,” the mayor says. “Two days later they arrived with their tanks and their bulldozers.”

Just hours after Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly linked to al Qaeda) had seized power in Damascus, Israel’s Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu ordered the army to “take control” of the demilitarised buffer zone in the strategic and water-rich Golan Heights, which overlooks northern Israel, Syria and Lebanon.

The 80-kilometre stretch was demarcated through a ceasefire deal between Israel and Syria in 1974, and has since been patrolled by the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF). Israel has long occupied large parts of Golan, which it annexed in 1981, but has – with the exception of Israel’s main ally the United States – never been recognised by the international community.

“The soldiers arrived and asked the imam to make a call (using the microphone he normally uses to call for prayer, editor’s note) to tell everyone to leave. They gave us until 3pm,” the village councillor recalls, noting it was the first time he had ever seen Israelis there since his arrival in 1978. “We made the women and children leave, but the men stayed.”

Maha* says she will never forget that day. “We didn’t even get enough time to get our things, barely enough time to bring clothes to wear,” she says, holding back the tears. “I stayed in Khan Arnabah for five days with the children before going back.”

Maha, who is in her 60s and worried that she and her family could be subject to reprisals if they don’t obey the orders, explains that in 25 years she has never seen Israeli soldiers in the village either. “How would you feel if you were told to leave your home overnight?” she asks, adding that she is afraid the army will come back and tell the villagers to leave their homes once again.

Almost half of villagers displaced

In just a few short hours, Al-Hurriyah was totally emptied of its women and children. Still, it was not until 10am the next day – long after the evacuation deadline had passed – that Israeli soldiers came knocking on the mayor’s door.

“They asked me why we hadn’t left with the imam. I told them I didn’t want to, and that I had nowhere to go. Then they threatened me, pointing a gun at me: ‘Next time, we’ll blow your head off!’,” Ahmed recalls as he counts the wooden beads of his misbaha, (prayer beads).

“We told them we were only shepherds and farmers, that they could search our houses and that we had no weapons to hide. They only searched my house and that of a bread seller.” Ahmed then did what he was told and left the village. Three days later, he received a phonecall and was told to return to Al-Hurriyah. “When I got home, there were around 20 armed soldiers there. They told me to bring everyone back [to the village], but they didn’t say why.” Some 600 villagers have since returned, but another 400 remain displaced in nearby towns like Khan Arnabah.

This is the same town where Bilal* goes to work every day. He is in his 60s and lives in Jubata al-Khashab, a village where the green military fatigues have become a daily sight since December 8. Only those who live there are allowed to enter. “The soldiers constantly come and go in the village,” he says, once again asking for reassurance that his testimony will remain anonymous.

“I’m afraid they’ll take my house. I don’t trust ‘the enemy’,” he says, adding there is now an obligation to return home early in the evening because “it’s dangerous”. Just like Maha, Bilal is also terrified of reprisals. He keeps touching his hands, most likely to stop them from shaking. “I don’t speak to them. I don’t know how they would react. I could be arrested,” he says of the Israeli troops, and reiterates that they “scare the villagers”.

‘Temporary’ Israeli occupation to ‘secure the borders’

In the past month, Israel has conducted hundreds of strikes aimed at destroying the Syrian military arsenal for fear it could otherwise fall into “hostile” hands. It has also conducted raids in large parts of the Quneitra province, searching for arms that the fleeing Syrian army might have left behind.

“They say we have weapons, but we don’t. There’s no armed group here,” Bilal says, adding that the Israeli troops “prevent people from moving around freely”.

This is the reason why Fatima Mansour decided not to return to Jubata al-Khashab. “I’ve been living in Khan Arnabah for 12 days now because I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to come and open up my shop every day,” she explains from behind the counter of her clothing boutique. “They’re only a kilometre from my house.”

Although Netanyahu has insisted that the presence of Israeli troops in Syrian Golan is temporary, most Quneitra residents believe it could in fact become permanent. Some 30,000 Israelis and 23,000 Druze with Israeli residency permits now live in the Israeli-annexed part of Golan. On December 15, 2023, Netanyahu’s government approved a project to double the Israeli population there for a total of NIS 40 million (€10.6 million).

{{ scope.counterText }}

© {{ scope.credits }}

“We think they want to take our land, but we won’t let them. We’ll stay in our homes,” Fatima says. Bilal agrees. “They want to expand, take as much land as possible from Lebanon, Palestine and Syria,” he says. “I’m afraid, but I want the world to know the true face of our enemy. They pretend to be the victims, but they’re the aggressors.”

As Syria tries to rebuild itself, the country’s new strongman Ahmed al-Sharaa, better known by his nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, has said that after years of civil war, Syria is “exhausted” and that the country is not in the state “to enter into new conflicts”. In Syrian Golan, these types of statements are enough to send shivers down Quneitra residents’ spines. “Inshallah, (if God wills) that the new government will discuss keeping our land within the 1973 limits,” Maha says. “I don’t want to leave my land in exchange for peace.”

This article has been translated from the original in French by Louise Nordstrom.

Leave a Comment