In the beginning there was Cimabue, “who was to shed the first light on the art of painting” – until he was “eclipsed” by his pupil Giotto.

The story, told by Giorgio Vasari in his “Lives of the Painters”, has for centuries been the standard account of the origins of the Renaissance, cementing Cimabue’s role as a transitional figure who paved the way for his more illustrious disciple.

Born in 1240, Cenni di Pepo, better known as Cimabue, is the first protagonist of Vasari’s 1550 classic, a survey of three centuries of Italian artistic genius – and Florentine self-promotion – leading up to Michelangelo. The tale of how he came to be eclipsed by Giotto had been told before by Dante in his “Divine Comedy”, begun shortly after Cimabue’s death in 1302.

Imagining a brief encounter with the painter in purgatory, Dante observed: “In painting Cimabue thought he held the field but now it’s Giotto has the cry, so that the other’s fame is dimmed.”

Such accounts have overshadowed not only Cimabue’s fame, but many of his achievements too, according to a landmark exhibition showing at the Louvre from Wednesday, which brings together restored and newly acquired works by the Florentine master.

“A new look at Cimabue: the origins of Italian painting”, which runs through May 12, offers a bold take on the pioneering artist who broke with the rules of Byzantine art, introducing the rudiments of expression and perspective. It contends that many of the innovations attributed to Giotto, and to the contemporary Sienese master Duccio, can be traced back to Cimabue’s work.

“Whether it’s Giotto’s naturalism or Duccio’s narrative verve, we can now see that both originated with Cimabue,” said the exhibition’s curator Thomas Bohl, for whom the show is certain to “challenge long-held assumptions about the origins of Italian painting”.

A long-lost masterpiece

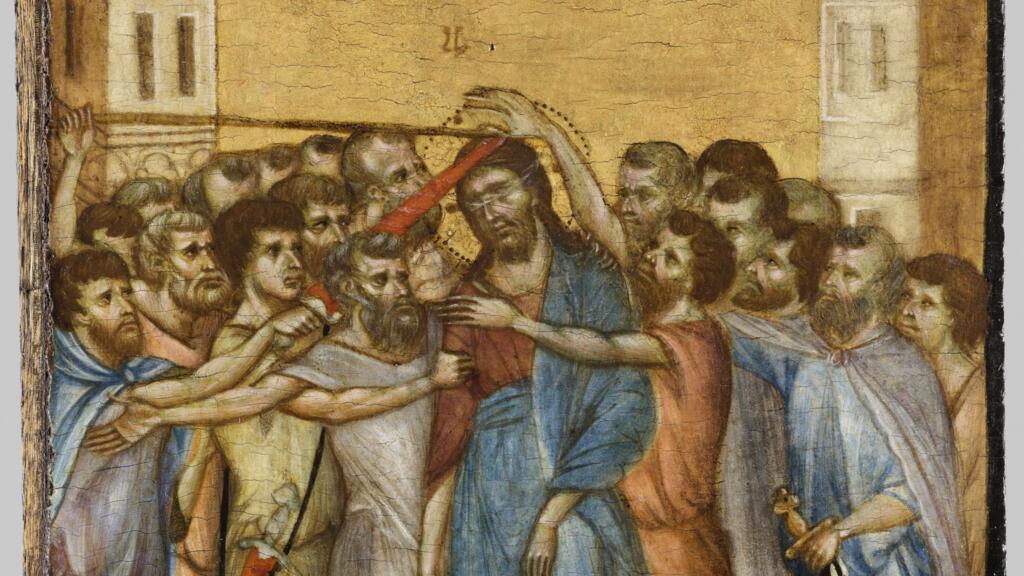

Cimabue’s Louvre reappraisal owes much to the chance discovery in 2019 of a small wooden panel depicting a scene from Christ’s Passion that had been hanging above the hot plate in an elderly woman’s kitchen in the town of Compiègne, north of Paris.

Measuring just 24 x 20 centimetres and painted in egg tempera, the unsigned painting caught the eye of a young auctioneer who had been asked to value the owner’s belongings and sift through a pile of junk bound for the dump. Exquisitely crafted, it bore the hallmarks of the work of late Medieval Italian artists, known in France as primitifs italiens, and appeared to have been sawed off a larger opus.

Following her hunch, the auctioneer took the painting to prominent Paris-based expert Eric Turquin, who stated with “certitude” that its author was none other than Cimabue, dubbed the “father of Western painting”, whose known works are so rare – and so jealously guarded – they had never been auctioned before.

When the panel was acquired by foreign buyers for €24 million later that year, the French government stepped in to block the sale, declaring the work a “national treasure”. The culture ministry was given 30 months to raise the funds to acquire the panel, with generous support from the Louvre’s private US donors, which is how Cimabue’s long-lost “Mocking of Christ” ended up at the world’s most visited museum.

Conveying movement and emotion

One of the painter’s most inventive works, the “Mocking of Christ” depicts the moment when Christ, blindfolded, is struck and derided by an angry crowd. Restored in time for the exhibition, the panel’s shimmering colours and lifelike figures evoke the violence of the scene.

“Never before had tensed muscles been painted in such detail,” said Bohl, highlighting Cimabue’s ability to convey movement and emotion.

The “Mocking of Christ” is part of an eight-panel diptych painted by Cimabue around 1280, of which only two other pieces are known: the “Flagellation of Christ”, part of the Frick Collection in New York, and the “Madonna and Child Enthroned between Two Angels”, found under a staircase in an English country house two decades ago and now at the National Gallery in London.

The three surviving panels have been reunited for the exhibition, which juxtaposes Cimabue’s works with masterpieces by Giotto, Duccio and other contemporaries, some of which had never left Italy before. The show also features paintings that were wrongly attributed to Cimabue two centuries ago during the plunder of Italian art by Napoleon’s armies, thereby highlighting the elusive nature of his surviving works.

Read more‘Glory of arms and art’: Napoleonic plunder and the birth of national museums

‘Maestà’ reborn

Napoleon’s haul did include one authentic Cimabue work, which, as the Louvre writes in its press release, has been described by art historians as the “founding act of Western painting”.

At more than four metres high, Cimabue’s sumptuous “Maestà”, which was taken from the Church of St Francis in Pisa in 1813, is the centrepiece of the exhibition, positioned in such a way that it is always visible – as if it were in dialogue with the other works.

The “Maestà” depicts an enthroned Madonna and Child surrounded by angels, with apostles, saints and other figures represented in the original frame. Years of conservation work have restored it to its former glory, bringing to light vivid colours, subtle features, and Cimabue’s pioneering use of transparency to reveal the figures’ limbs beneath their clothes – a technique commonly believed to have originated with Giotto.

An earlier work than the “Mocking of Christ”, the restored “Maestà” shows how Cimabue had already opened the way for naturalism in Western painting, breaking with the conventions of Byzantine iconography to introduce perspective, three-dimensional spaces, bodies in volume and articulated limbs.

“The point is no longer to represent the idea of a face, as in traditional iconography, but rather the face itself, with its anatomy, texture, colours and the way light is reflected,” Bohl explained. That endeavour aligned Cimabue with his Franciscan patrons, keen to “render saints more accessible, represent them as embodied humans, so the faithful could identify with them”.

Ushering in what Bohl termed an “artistic revolution”, Cimabue made innovation a central element of artistic creation. From then on, the curator concluded, “painters would compete to invent new ways of producing the illusion of life in painting, while seeking to stand out among their contemporaries”.

“A new look at Cimabue: the origins of Italian painting” runs through January 22-May 12, 2025 at the Louvre in Paris.

Leave a Comment